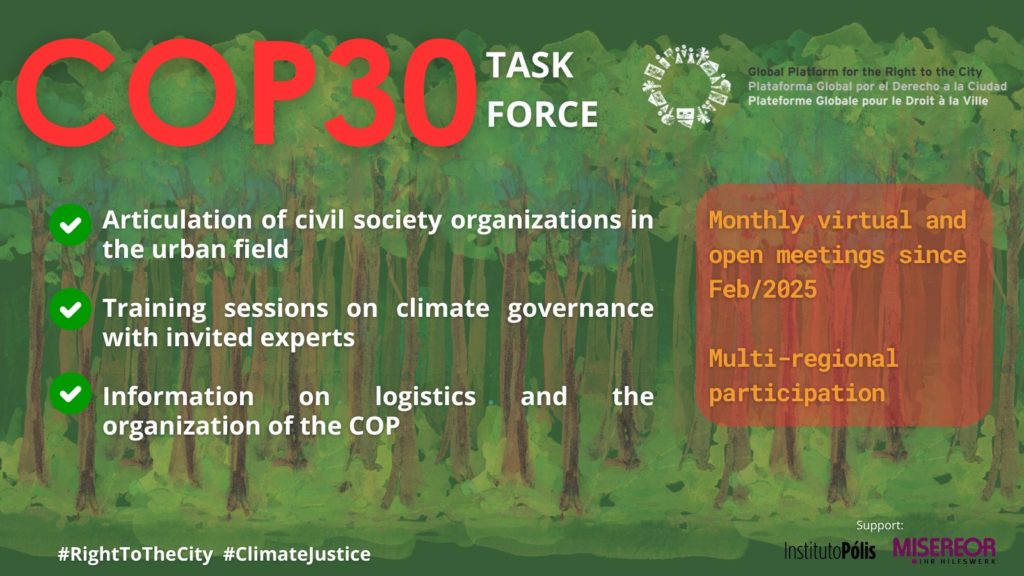

The Global Platform for the Right to the City (GPR2C) took to COP30 the vision that there is no Climate Justice without the Right to the City. The first climate conference to be held in Brazil took place from November 10 to 21, 2025, but preparations for our arrival in Belém do Pará began much earlier. Throughout this year, we held 9 meetings in a task force that involved training, creating a common agenda and strategies to strengthen the presence and participation of urban social movements and partner organizations at the COP.

We saw the conference as an opportunity to leverage the construction of a multi-actor, multi-level task force for climate action, led from within communities. The GPR2C defined its joint agenda for COP30 in three strategic axes:

- Boosting effective community participation in mitigation, adaptation and implementation plans for the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), recovering traditional and community knowledge.

- Decentralize and leverage local climate finance, directing funds for loss and damage and adaptation to community-led initiatives, and promoting community oversight of multilateral mechanisms.

- Promote a just transition, protecting basic services (including their deprivatization) and ecosystems, and supporting the social and solidarity economy.

The focus on Climate Justice and the Right to the City is justified because the former recognizes the structural inequalities that disproportionately affect marginalized populations and are deepened by climate change, and the latter offers the necessary lens to approach the climate crisis from a territorial and social justice perspective.

The GPR2C’s campaign at COP30 is detailed on a special page on our website, one of the fruits of the platform’s efforts towards the conference.

Events

We reinforced our commitment to the Right to the City and Climate Justice at COP30 by organizing and participating in various events. Here are some of the highlights:

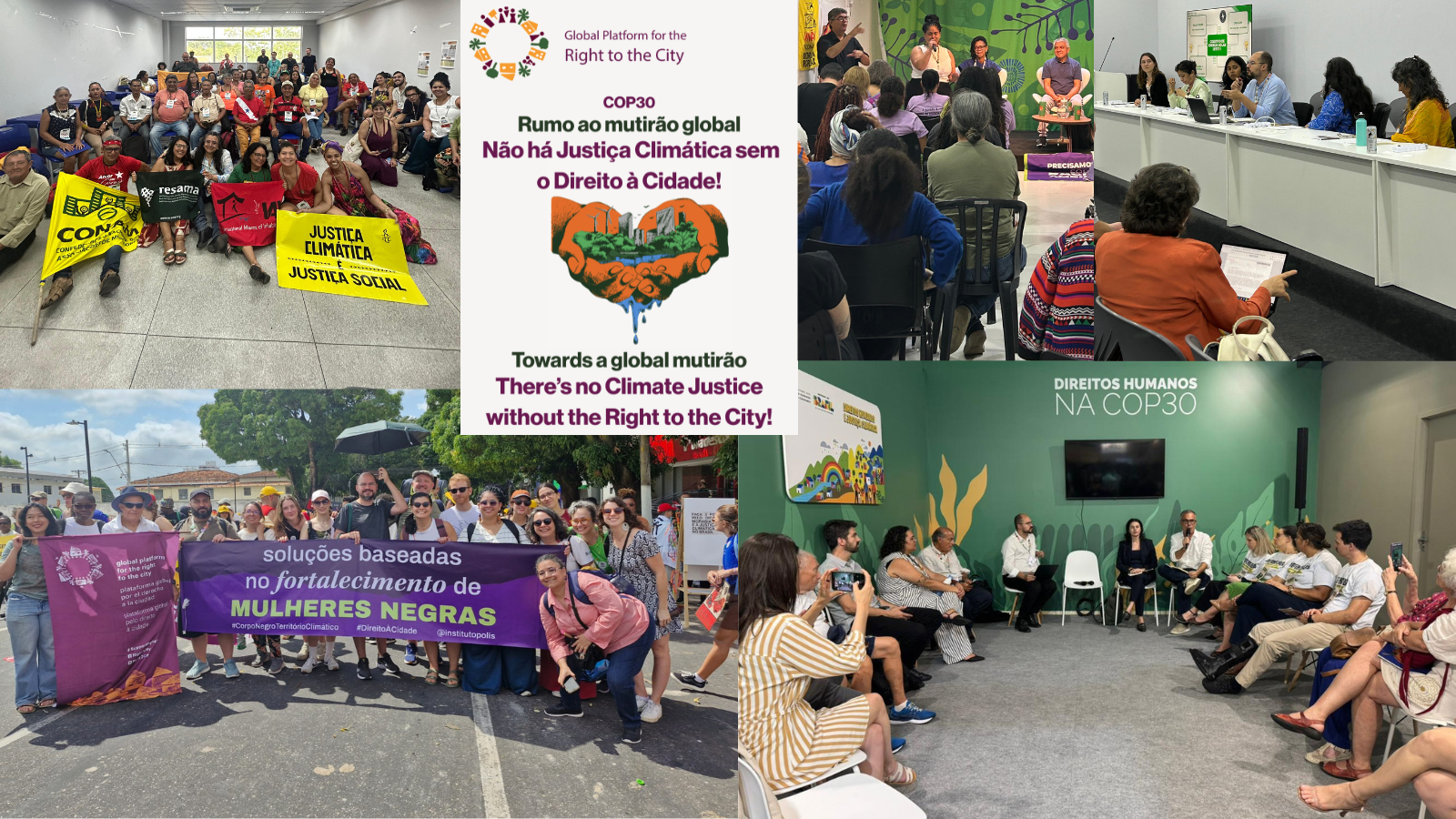

Urban Plenary: convened by GPR2C, Pólis Institute, the National Forum for Urban Reform and Abong, and held at the NGO House, the Plenary brought together social movements and civil society organizations to articulate narratives and advocacy strategies, leveraging the demands of local communities. The event was relevant in terms of the multiplicity of voices represented. Present, for example, were black women’s movements, housing movements, local authorities such as São Paulo councillors Nabil Bonduki and Renata Falzonial and UN-Habitat’s executive director, Anacláudia Rossbach.

Urban Plenary: convened by GPR2C, Pólis Institute, the National Forum for Urban Reform and Abong, and held at the NGO House, the Plenary brought together social movements and civil society organizations to articulate narratives and advocacy strategies, leveraging the demands of local communities. The event was relevant in terms of the multiplicity of voices represented. Present, for example, were black women’s movements, housing movements, local authorities such as São Paulo councillors Nabil Bonduki and Renata Falzonial and UN-Habitat’s executive director, Anacláudia Rossbach.

Official Side Event: Held in the Blue Zone, co-organized by Instituto Pólis, WIEGO, YUVA, HIC-AL, Misereor and Mahila Housing Trust, the panel “Promoting community-led initiatives and climate justice in the IPCC Report on Climate Change and Cities” connected scientific evidence and practical experiences of community-led mitigation and adaptation with the participation of experts from the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) itself, with the aim that this bottom-up evidence will also be considered in the production of the report that will be released in 2027. The IPCC experts stressed the importance of these experiences and also indicated that civil society must be an ally so that the report that will be released can reverberate in different spheres and influence decision-making on climate action.

Official Side Event: Held in the Blue Zone, co-organized by Instituto Pólis, WIEGO, YUVA, HIC-AL, Misereor and Mahila Housing Trust, the panel “Promoting community-led initiatives and climate justice in the IPCC Report on Climate Change and Cities” connected scientific evidence and practical experiences of community-led mitigation and adaptation with the participation of experts from the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) itself, with the aim that this bottom-up evidence will also be considered in the production of the report that will be released in 2027. The IPCC experts stressed the importance of these experiences and also indicated that civil society must be an ally so that the report that will be released can reverberate in different spheres and influence decision-making on climate action.

The GPR2C also actively participated in the unified Global March for Climate Action, alongside more than 70,000 people, raising the banners of Climate Justice, the Right to the City and climate solutions based on empowering black women. The March was called by the People’s Summit, an initiative mobilized by social movements, which took place in the first week of COP 30, with various activities at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA).

The GPR2C also actively participated in the unified Global March for Climate Action, alongside more than 70,000 people, raising the banners of Climate Justice, the Right to the City and climate solutions based on empowering black women. The March was called by the People’s Summit, an initiative mobilized by social movements, which took place in the first week of COP 30, with various activities at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA).

The platform also promoted the “Right to the City and Climate Justice” panel at the People’s Summit, as well as debates on the New Urban Agenda at the Cities and Regions HUB in the Blue Zone, and discussions on the Inter-American Court of Human Rights Opinion on the climate emergency at the Human Rights Pavilion in the Green Zone.

The platform also promoted the “Right to the City and Climate Justice” panel at the People’s Summit, as well as debates on the New Urban Agenda at the Cities and Regions HUB in the Blue Zone, and discussions on the Inter-American Court of Human Rights Opinion on the climate emergency at the Human Rights Pavilion in the Green Zone.

Legacy of COP30: between advances and failures

The relevance and diversity of these events, however, were not reflected in the final decisions of COP30. While the conference made some important advances, it failed to significantly address the Right to the City and Climate Justice agendas in its final text.

Advances

- The agreement to develop the Belem Action Mechanism (BAM) for a Just Transition was the highlight. The instrument, which has yet to be operationalized, is the first to formally recognize the role of frontline communities in defining transition paths. However, its effectiveness will depend on adequate, public, non-debt-generating climate finance protected from corporate capture, ESCR-Net stressed.

- Negotiations on the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), one of the priorities set for this COP, resulted in the approval of 59 adaptation indicators, reducing the initial forecast of 100 indicators. Although its adoption is voluntary on the part of the countries, it can be considered a step forward as it places the debate on adaptation at the center of climate action and indicates the need for specific funding for the issue.

- For the first time, Afro-descendants were mentioned in the final texts of a COP, such as the Just Transition, the Gender Action Plan (GAP) and the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), another advance in relation to the Climate Justice agenda.

- The Belém Gender Action Plan (GAP) (2025-2034) included the historic recognition of women environmental human rights defenders and care work. However, the instrument was criticized for its lack of a cross-sectoral framework, low gender diversity and the absence of direct funding for climate-sensitive actions, pointed out Ranjana Giri of the Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development (APWLD). Governments such as Russia, Argentina and Paraguay were pushing to restrict the definition of “gender”, which would represent a decades-long regression in UN language and weaken the effectiveness of climate action, pointed out the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

- The issue of cities gained significant visibility on the agenda. The conference marked the recognition of urban planning as a decisive arena for climate implementation. The Ministerial Meeting on Urbanization and Climate Change (co-organized by UN-Habitat and Brazil’s Ministry of Cities) adopted a Chair’s Summary that outlined 8 key areas for action:

- institutionalizing the Ministerial Meeting in future COPs.

- strengthening the participation of sub-national and local governments in UNFCCC processes.

- strengthening the New Urban Agenda, explicitly integrating issues such as adaptation, mitigation, loss and damage, just transition and climate finance.

- use of the IPCC Special Report on Climate Change and Cities to inform the Global Stocktaking and support the development of local capacities.

- incorporating sustainable urban development priorities and multi-level climate action into deliberations on the Global Goal on Adaptation and Just Transition.

- increasing urban content in national instruments (NDCs, NAPs, LT-LEDS).

- increasing climate finance for the local level, ensuring that funds reach projects on a municipal scale and communities.

- Promoting equity and inclusion for the urban poor and residents of informal settlements, as a central dimension of the just transition.

- Cities axis at the People’s Summit: For the first time in history, the People’s Summit had a cities axis articulated by popular movements, which is a significant gain in the popular struggle, even if the official COP did not fully incorporate the agenda. The Summit produced a final declaration which was presented to the Brazilian Minister for the Environment and Climate Change, Marina Silva, and to the president of COP30, André Corrêa do Lago. In item 6, the text mentions the defense of “direct consultation, participation and popular management of climate policies in cities”.

Failures

- One of the major setbacks was the inclusion of an indicator, 7b, in the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) that indicates the “proportion of infrastructure and human settlements vulnerable to climate disasters and other extreme events relocated to a safer location”, thus justifying removals due to climate factors. This issue generated mobilization from civil society and questions from Brazilian negotiators, but the indicator remained.

- The visibility of the issue of cities at COP30, although strong in the Brazilian Presidency, in ministerial and alternative spaces, made no headway in the outcome document, which did not present any significant innovations with regard to the role of cities, limiting itself to reproducing a paragraph that has existed since COP28, which recognizes the important role of cities in tackling climate issues. The paragraph places various actors (such as civil society and sub-national governments) on the same level, resulting in a superficial emphasis on cities in official documents.

- The conference failed to make progress on the transition away from fossil fuels, with the road map left out of the final agreement at an event heavily attended by fossil industry lobbyists. The COP Presidency has indicated, however, that throughout the remainder of its mandate until COP31 in 2026, it will lead the process of drawing up the Belem Roadmaps for the Fossil Fuel Transition.

- “Without binding international rules, such as those established by the Binding Treaty on Transnational Corporations and Human Rights, to curb corporate power and prevent states and companies complicit in human rights violations from influencing climate decisions, the results of the COP will continue to fall short of the justice that communities demand,” ESCR-Net stressed. To ensure Climate Justice, recent decisions by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the Inter-American Court must be put into practice, according to which historical emitters have an obligation to prevent future damage, ensure accountability and support community-led solutions.

Importance of COP30 for the GPR2C

It was the first time that the GPR2C organized itself in a more structured way for strategic and active participation in a COP, which produced very satisfactory results in terms of political advocacy, dissemination of knowledge and articulation of partners.

- Prior preparation process: The task force’s preparatory process, which lasted almost a year, was one of the platform’s best strategic decisions, adding members and new partners, and providing qualified information content to strengthen its participation in the Conference. As a result of this process, the GPR2C was recognized by partners as a network that succeeded in broadening the connection between the Right to the City and the debate on Climate Justice.

- Articulation of different actors in the urban field: The GPR2C also played an important role in spaces outside the so-called official COP zone, the Blue Zone. By co-organizing events at the People’s Summit and the NGO House, it was also able to gain recognition among urban social movements and other civil society organizations. It also consolidated its partnership with Brazil’s National Forum for Urban Reform, drawing up a joint position paper.

- The GPR2C’s communication achieved greater visibility with the distribution of printed materials, such as the Climate Change Glossary and the folder with our common message for COP30, as well as the reactivation of its presence on social networks, with the dissemination of key messages and events.

Future priorities

The post-COP30 evaluation points out that the movement created by the mobilization towards COP30 must be strengthened and continued, as there is still a lot of collective work to be done to effectively consolidate cities at the heart of climate action. Future priorities include:

- Monitoring the Adaptation Indicators: drawing up a collective strategy on how to influence indicator 7b, which suggests removing populations from risk areas. Climate change cannot be a justification for the removal of vulnerable populations, and a truly fair adaptation target must cross the debate on better housing conditions and urban infrastructure, based on the right to the city.

- WUF 13: take advantage of the 13th World Urban Forum, in May 2026, to debate the revision of the New Urban Agenda (NUA), which will be 10 years old in 2026, centrally including the issue of climate justice.

- Impact on the IPCC Report on Cities: continue exploring possibilities for impact on the IPCC report on Climate Change and Cities, which will have a first version by May 2026. The idea is that WUF13 can also be a space for advocacy on this issue.

- Roadmaps: to influence the debates on the development of roadmaps – both on the transition from fossil fuels and on forests – which will be led by the Brazilian COP Presidency until COP31, from the perspective of the Right to the City and Climate Justice.

- Integration of International Law and Climate Justice: Explore the repercussions and obligations generated by the opinions of the International Court of Justice and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights on the climate emergency and the obligations of governments.

Although the leaders of the richest nations failed to live up to the ambition and popular demands in Belém, the social mobilization and articulation achieved by the GPR2C demonstrated the potential of the Right to the City as a transformative and mobilizing framework for Climate Justice.