This article has been collaboratively written by GPR2C members and allies, see more at the end.

In today’s challenging context, with the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, longstanding structural inequalities have become strikingly apparent. This scenario is not new and existed long before the new coronavirus arrived. However, these inequalities have often remained invisible to many sectors of society, including public policy decision makers. With the emergence of COVID-19, pre-existing and emerging inequalities, both at the urban level and in other dimensions, have become visible, amplified and deepened.

Right now, cities are the main points of concentration of the effects that this virus has produced worldwide. On the other hand, cities (which in Latin America concentrate 80% of the population) are also the places where we find the greatest capacity to respond to this situation due to the existence of different actors and opportunities for a possible virtuous articulation between them.

Despite the fact that cities concentrate the greatest impacts of the epidemic, the way in which the context is experienced is affected by the multiple inequalities that characterize Latin American and, as it is to be expected, it is the most vulnerable sectors that bear the worst consequences.

Among the groups most affected by the multiple impacts of the epidemic is the population of precarious settlements, which represents approximately 20% of the region’s urban population. These are, according to María Cristina Cravino, large urban fragments without the status of cities, traditionally invisible, lagging behind and excluded from the opportunities of urbanization. Understanding how the epidemic has been lived through from the experience of the communities and organizations of the popular habitat is fundamental to engaging in a reconstruction capable of facing the effects of the health epidemic while, at the same time, to addressing long standing social and economic debts regarding the most vulnerable communities within Latin American cities.

A housing laboratory to identify paths forward

In this scenario, different groups and grassroots organizations, academics, professionals, among others engaged within regional and international articulation have converged in a virtual space to continue learning, sharing experiences and exchanging knowledge to analyze the situation and possible steps to follow. The challenge we set ourselves was to identify paths forward based on the knowledge and recognition of collective efforts from neighborhoods, territories and communities of different countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.

With these purposes, we convened and organized a Housing Laboratory (LAV) on Slums and Covid-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean. The meeting was attended by representatives from 16 countries, members of grassroots and community organizations, non-governmental organizations, academics, networks and international platforms.

The protagonists of the dialogue were community-based leaders. In particular, an exchange of experiences and analysis was generated on how these organizations are responding, from the very beginning, to the additional challenges that COVID-19 has placed on the communities of popular neighborhoods and precarious settlements.

It is clear, despite not being evident to all eyes, that the conditions of pre-existing inequalities in popular neighborhoods and precarious settlements have caused them to be greater impacted by the emergence of COVID-19. While the message disseminated in most countries focused on how this virus affects all people without discrimination, this is not entirely true. The groups most impacted by the effects of the epidemic, are exactly those which were already experiencing deficiencies in the enjoyment of their rights, specifically concerning their right to housing and right to the city. They are also the ones who have responded swiftly to the situation, with collective efforts and community work.There are several common points in the analysis of the different situations in the countries of the region. In the face of general recommendations from national and international institutions regarding isolation and hygiene, it was quickly pointed out that this was not possible for millions of people in the region (and the world). “#StayAtHome” was not, and is not, possible for people who live in precarious housing and neighborhoods, without basic services, where there is overcrowding and where conditions associated with the habitat, such as access to water and sanitation, are not guaranteed. Nor was it possible for millions of informal workers who depend on going out to earn a living every day. So, without putting forward actions to respond to the wider challenges posed by the pandemic, it is very difficult for the population to self-isolate in order to protect itself and survive the health and social emergency unleashed by the pandemic.

Community responses to the crisis

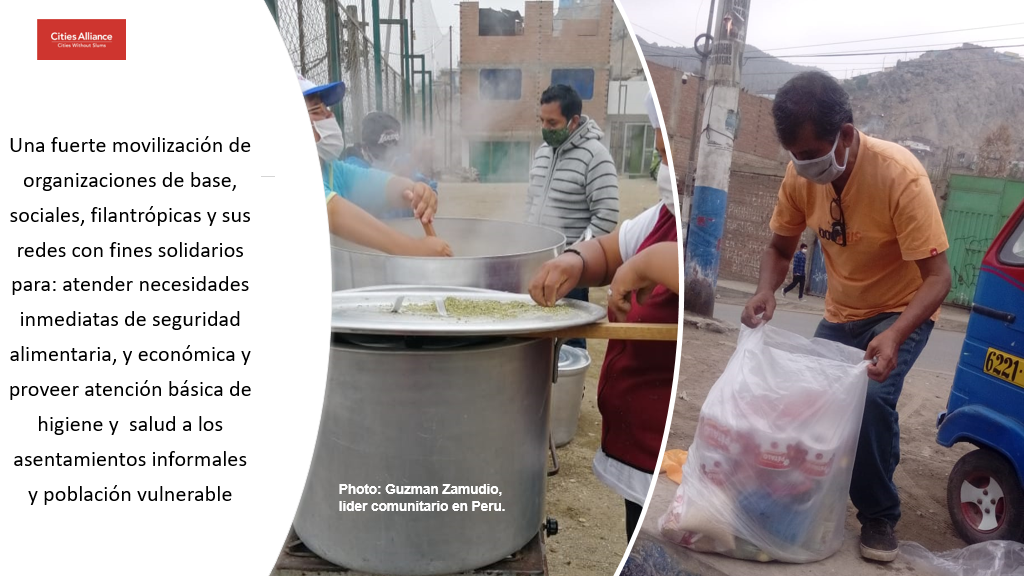

In the face of shortages and limited measures taken by some national or local authorities, grassroots organizations have been on the front line, taking action for their communities by taking the lead, but also by denouncing and demanding action from the State. Creatively proposing and implementing community measures that have made a difference for millions of families.

Source: Cities Alliance

In this sense, the testimonies of colleagues from different countries during the conversation have contributed to collective thinking and sharing of knowledge needed both to face the day to day challenges but also to generate action and advocacy responses. It was a key space to think about recovery and towards which cities and territories we want to advance in the future.

From Argentina, La Garganta Poderosa raised the need to make visible the structural needs of the neighborhoods and popular settlements. The slums face increased sanitary risk due to the living conditions, the lack of infrastructure and the precariousness produced by the lack of urbanization and the lack of basic services. The conditions of overcrowding, the lack of water, the deficient electricity service and the lack of adequate hygiene supplies were highlighted. The main demand is linked to “integral accompaniment”. This would mean monitoring the entire epidemiological chain, as well as a comprehensive approach to the urban and housing conditions of the neighborhood. For example, the policy based on identifying positives to the virus through testing does not contemplate that, once the case is identified, the population does not have the conditions to continue a process of isolation and social distancing.

In the absence of the State and following local traditions and experiences, community organization is strengthened. “As territories, as neighbors, we are in the front line, we are taking care of ourselves collectively”. For example, with a network of psychologists, social promoters who provide information to the inhabitants of the neighborhood, soup kitchens, dining rooms, etc. Likewise, there are self-management initiatives such as La Garganta Poderosa Magazine (an alternative communication space) and the House of Women and Dissidents, among others.

Community leadership in face of a limited state response

Source: Ruben Perez Flores, Red de Ollas Comunes Metropolitana, Lima, Peru

In this sense, it is important to recover two dimensions. Firstly, the need to implement public policies from the State that guarantee the necessary income so that the inhabitants of these popular settlements can protect their health and reduce circulation and exposure to the virus. Secondly, it is clear that overcrowding makes social distancing difficult and that informal and precarious workers need income on a daily basis. But the persistence and power of community social organization cannot be underestimated, also to ensure prevention, if necessary, through isolation or distance. The inhabitants of the popular neighborhoods comply by creating alternative arrangements for care and prevention. For example, by implementing social distancing and community health prevention strategies in common spaces such as schools, clubs or dining halls. Also by collectively supporting the needed transits within the neighborhood and communally preserving populations at risk.

In addition to the impacts on public health, the coronavirus epidemic has accelerated the economic crisis in the region and community organizations have had to redouble their efforts to ensure their livelihoods and economic development. In this regard, the Popular Urban Movement has highlighted the importance of popular economic networks within Mexico City, which, through various solidarity economy mechanisms, have been able to respond to the economic effects of the epidemic. This has allowed for attention to be given to the migrant population, indigenous people, and people living on the streets, among other sectors that have traditionally been victims of urban exclusion.

In this context, at the center of community organization, the organizations agree to highlight the role of women as the main actors in the articulation of initiatives within the community and in coordination with other public and social actors. In this line, from the Intercommunity Association of Health, Education and Environment (AISEMA), the effect of the deepening of gender inequalities is highlighted, which at the same time has increased the burden of women in terms of care work and worsened the precarization of working conditions, it has also charged them as community leaders, with the main responsibilities of the health, economic and social response to the epidemic.

This community response, in many cases, has had to face an escalation of institutional violence by the police forces in particular and from different public institutions in general. This has been stated by the Union for Popular Housing in Brazil, who shared that the reaction to the pandemic has been accompanied by an increase in human rights violations, which have affected the poorest sectors of the cities and, within these, with greater intensity the black population – especially young people – and women.

In summary, despite the fact that state responses and the relationships established with the communities vary from case to case, there is agreement in identifying the weakness of a timely, inclusive and effective response by the state, in the face of which the inhabitants of slums highlight community organization as the first line of response to the multidimensional crisis. On the other hand, the lack of effectiveness evidenced is also a reflection of structural weaknesses of our States to guarantee equality and common welfare, among which the fragmentation of government levels and sectors, the absence of a territorial approach to urban policies and the lack of capacity of social policies to adapt to the multiple diversities that make up Latin American societies have been highlighted.

Towards new models for ‘building back better’

With a view to a recovery process that allows for ‘building back better’, from different points of view there were calls for what we could call a process of resilient reform of the post-pandemic State in the key of human rights that, on the one hand, allows the development of capacities to prevent future health crises and, at the same time, lays the foundation for a new development model with greater and better presence and a commitment to the public.

Among the lines of work mentioned to advance in this process of public reengineering policies in all areas and, those related to the urban sphere in particular, the Global Platform for the Right to the City has called for the construction of a new municipalism, in which multiple approaches and identities converge to build an alternative city project based on the social function of habitat and territory, defense of common goods, and the radicalization of local democracy, among others.

Source: Ruben Perez Flores, Red de Ollas Comunes Metropolitana, Lima, Peru

Taken to the level of sustainable recovery process management, the need for intertemporal urban planning was raised, capable of combining and exchanging strategies and actions for response and recovery to the extent that coexistence with the virus and its multiple social manifestations will evolve. Likewise, the call to break the silos of public management in order to build and implement inter-institutional, inter-level and intersectoral urban policies, organized around a territorial approach that recognizes the multiple scales on which the urban phenomenon operates and the impacts it has on the popular habitat, was highlighted.

This new generation of urban policies must take as a base the experience built through years of resistance by communities of precarious settlements and popular neighborhoods in general. This experience, as it was expressed in the dialogue and we have wanted to summarize in these lines, has not only been the articulating axis of the response to the emergency, but has also shown that there are alternative ways of building cities and of relating among inhabitants and with our environment. It is a matter of a cumulus of popular experiences that through the daily practice of subsistence, resistance and transformation of the habitat, points to the fact that another city is possible and it is urgent to build it.

Along these lines, the LAV left open doors to continue imagining, debating and building synergies for solidarity, through a space of open and diverse exchange for Latin American urban praxis and, we hope in future editions, the Global South.

Among these lines, clearly stand out:

- To continue on promoting and giving life to these spaces of regional and international articulation, with the voices of neighborhood leaders, in order to keep on exchanging and learning together. These spaces are not new, but it is still a challenge to strengthen and experiment with diverse and new ways of making visible the knowledge accumulated in the territory, as well as to strengthen the actions and solutions that the inhabitants of the neighborhoods put into practice in the face of emergencies such as COVID-19;

- Keep on invigorating the alternatives that grassroots organizations have coined for several decades and that, in some cases, have managed to influence urban policies that incorporate more inclusive and sustainable visions such as solidarity economies, food sovereignty, and attention to structural violence with a gender perspective, among others;

- Continue the dialogue in order to understand how to move towards cities and societies based on care, recognizing the fundamental role of women and working towards co-responsibility. They have been and still are the ones who mostly take care of homes and communities -caring economies- an unpaid work that allows the daily survival of people. Women in the region have been the most economically vulnerable to the COVID-19 pandemic, occupying the sectors with the greatest economic contraction and 60% of informal jobs, in addition to being the most prone to extreme poverty and food insecurity (UN Women, 2020). Recognizing and redistributing care jobs and improving women’s income and working conditions is a priority within urban neighborhood networks and communities, international cooperation, academic and government.

The other major theme, widely discussed during this Urban Laboratory, is the need to continue to find ways to influence and form alliances between grassroots organizations and the various actors, sectors and levels of action that make decisions about urban territories. Thus, a key challenge is to encourage and promote inclusive governance that supports existing alliances, those emerging during the COVID-19 crisis, and the formation of new ones -not from the bottom up or from the top down-but through processes that foster relationships of trust and solidarity among peers. These multilevel, intersectoral and inter-institutional alliances become essential to integrate, diversify and direct post-COVID-19 funds, financing and public policies towards the populations and inhabitants most affected and vulnerable, not only by the pandemic but also by structural conditions.

Finally, it was recognized that promoting a transition towards more inclusive cities based on the right and social function of habitat is a learning process in which there is no single response; therefore, the next steps will be built collectively and through constant processes of dialogue, co-production of knowledge, negotiation and renegotiation, as well as through the articulation of new networks and their diverse responses. Undoubtedly, these dialogues will have to be aimed at putting at the center people and life, not only that of human beings but of the planet. This will be the way to face and overcome the increasingly recurrent and intertwined crises: health, economic, climate and environmental, migratory, among others.

Authors:

- Luis Bonilla Ortiz-Arrieta. Economista y Magíster en Estudios Políticos y Sociales Latinoamericanos. Miembro del Grupo de Trabajo “Desigualdades Urbanas” de CLACSO.

- Ivahanna Larrosa. Arquitecta, Maestranda en Ordenamiento Territorial y Desarrollo Urbano de la Facultad de Arquitectura, Diseño y Urbanismo de la Universidad de la República, UDELAR (Uruguay), Investigadora del Centro Interdisciplinario de Estudios sobre el Desarrollo- Uruguay (CIEDUR).

- Karol Yáñez Soria. PhD Desarrollo y Planeación por Development Planning Unit, University College London. Investigadora Cátedra CONACYT. Adscrita a CentroGeo México.

- Pablo Vommaro. Historiador. Doctor en Ciencias Sociales, Profesor de la Universidad de Buenos Aires e Investigador del CONICET. Director de Investigación de CLACSO.