Henri Lefebvre, despite having made a decisive contribution to how we understand cities today, is an intellectual to whom little justice has been done.

Almost three decades ago, on 29 June 1991, the philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre died in the French town of Navarrenx. Lefebvre was a philosopher who accompanied the historical events of May 1968 with his thoughts and even anticipated them: that same year he would publishhis most famous and translated book, Le droit à la ville, shortly before the urban protests broke out in the Parisian periphery of Nanterre

This year marks the 50th anniversary of this publication. Many activities and debates have been organized, both in France and abroad, to discuss the right to the city, its relevance today and how it has been tried to be put into practice. All these reflections are very pertinent, not only because the right to the city has been claimed for several decades as an alternative to the hegemonic, excluding and segregated urban model, but also because Henri Lefebvre, despite having made a decisive contribution to the way we understand cities today, is an intellectual to whom little justice has been done, both in life and after his death. Lefebvre was a misunderstood and ignored thinker in his time; subsequently forgotten; and now only partially studied.

Perhaps the reason for this is that Lefebvre was not a conventional thinker, not only because of his scientific production, but also because he was not an ordinary intellectual. Until the age of 28, he worked as a salaried worker at Citroën and as a taxi driver in Paris. At that age he began to work as a high school teacher and it would take two more decades for him to begin his scientific work: first as director of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (1949-1961) and then as a university professor (1961-1973). His academic career, despite being late (he was already 60 years old), was extremely productive: some thirty books signed by him were published.

In the same way that his professional trajectory was not conventional, neither was his scientific thought. Lefebvre reflected on the basis of a heterodox approach that was alien to the intellectual currents of the time, such as structuralism or post-structuralism. Moreover, for some (such as Sartre), his status as a militant Marxist in the French Communist Party made him the object of strong criticism. And, for others (the orthodox Marxists), his condition as an independent philosopher who did not submit to the ideological determinations of the party generated rejection. This probably explains how unnoticed his work has gone in France.

Outside the country, the situation has been more unequal. His work has been translated into several languages (German, Korean, Spanish, Japanese, English, Portuguese and Serbo-Croatian), but only a few very concrete parts, especially those related to the urban. In the United States and Brazil, Lefebvre has had an important theoretical impact, while in Europe it has fallen considerably into oblivion. This divergence between its reception inside and outside Europe is clearly demonstrated by analysing the Portuguese-speaking context. In Brazil, entire research laboratories and university departments are devoted to the work of Lefebvre. In Portugal, on the other hand, it has been considerably ignored by publishers. Something similar has happened in the Spanish context.

Both in France and in the European context as a whole, it would take until the end of the 2000s for a new generation of European researchers to resume their work systematically. However, in spite of these attempts to analyse the totality of Lefebvre’s thought by some intellectuals, the fact is that the most well known and studied writings are those that deal with the urban. Nevertheless, the philosopher reflected on issues as diverse as modernity, capitalist culture, the State or political participation. And he did so, moreover, from the most varied disciplinary fields: philosophy, political science, language theory or sociology. Perhaps because of this eclectic gaze it ended up being ignored by continental philosophy.

With regard to the analysis of cities, Lefebvre was a pioneering thinker who reflected on the city, on the social production of space and on everyday life. He conceived of the urban as the result of the dialectical relationship between time and space, a relationship that manifested itself in a particular way in everyday life and in the uses of the city. But not only that: Lefebvre claimed the “living city”, that is, the processes of social significance, ignored by urban professionals (such as architects or town planners), who favoured the “material city”, that is to say, planning, buildings, urban form.

The symbolic content of streets and squares

From this point of view centred on social practices, Lefebvre drew attention to the importance of understanding the city not only from the point of view of its physical materiality, but also as a “social construction”. An approach in which what could be called urban intangibles acquire centrality: the way of life of the inhabitants, their use of time, encounters, the collective imaginary, identities or historical memories, among others. Elements that, undoubtedly, are shaped by the material city, since urban form influences the type of social relations that can be established in a given territory. But which, in turn, shape it by endowing streets, squares and neighbourhoods with symbolic content and social significance.

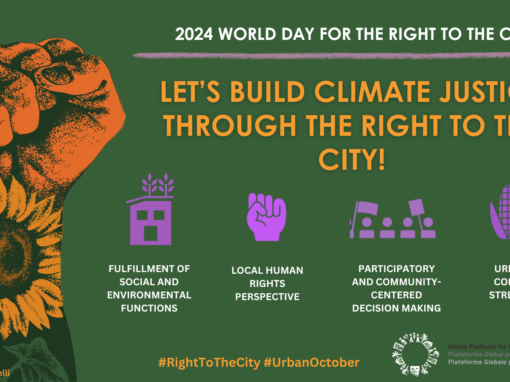

For Lefebvre, then, the “right to the city” consisted fundamentally in guaranteeing the “right to urban life”, to fill the space in which you live with flows, relationships and experiences. In short, the right to appropriate the city and to build it collectively from everyday life and social and cultural practices. Lefebvre’s theoretical proposal also asserts the importance of the political agency of the inhabitants and the demand for better material living conditions, especially for the urban peripheries.

Despite this integral view of the urban vertebrate in its different dimensions (material, political and social), the truth is that many of the interpretations made of the right to the city have paid less attention to its reading as “the right to urban life”. That is to say, the way in which this concept has historically been claimed in social mobilizations and is attempted implementation through institutional policy has very often overlooked the importance of urban ’intangibles’, of the sociomorphological dimension of the city.

The immediacy of action required to respond to the material needs of city dwellers is not trivial. Nor is it the case that our cities have a solid democratic legitimacy. However, it should not be less important to preserve cities as spaces of social production and symbolic goods. For this, it is essential to protect culture, public space, neighbourhood life and, in short, the existence of cities on a human scale. Cities that can be walked, cycled, and played in. Cities for life.

Article by Eva Garcia Chueca, CIDOB.

Original source El País, own translation: https://elpais.com/elpais/2018/07/16/seres_urbanos/1531735986_176681.html