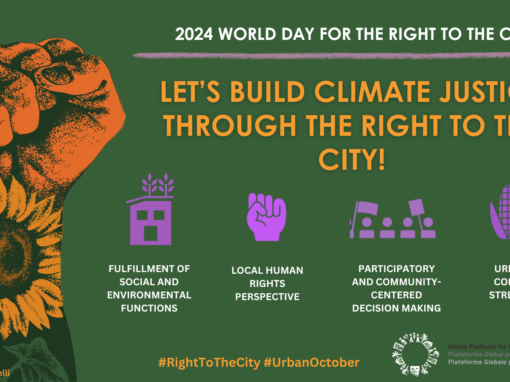

The Right to the City is a collective demand and agreement on the need to implement the Global Agendas for Sustainable Development with a human rights approach.

“In his book “The Invisible Cities”, Italo Calvino asked this question in a work dedicated to urban spaces, spaces that were already becoming uninhabitable in 1972. In Calvin’s words “the crisis of the city too great is the other side of the crisis of nature”. In this sense, the Right to the City, a term that although in vogue represents a political flag claimed for many decades by civil society, defends a new paradigm of cities, towns and human settlements based on the principles of social and spatial justice, equality, democracy and sustainability. This is not an apology of infinite and unjust urban growth, but of the need for a profound change to guarantee a dignified life in each territory.

We would then add toItalo Calvino’s question :what are cities and human settlements for us today? or rather: what should they be?. With this question we refer to the Agenda 2030 Declaration which includes a Sustainable Development goal dedicated to sustainable cities and human settlements, OSD 11: “Making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”. This commitment, signed by 193 states in 2015, declares the desire to achieve “a world of universal respect for human rights”. Therefore, cities should be the reflection of this world, and it is precisely what the Right to the City defends: common territories, territories of rights, managed by and for all.

The New Urban Agenda (NUA), the roadmap for cities embodies the world’s commitment to sustainable urbanization, signed in 2016 is in line with this. The NUA states that cities and human settlements should be those spaces where “all people can enjoy equal rights and opportunities, as well as their fundamental freedoms, guided by the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations, including full respect for international law”. This agenda includes the Right to the City in its paragraphs 11 and 12, sharing the ideal of “a city for all, in terms of equal use and enjoyment of cities and human settlements, seeking to promote integration and ensure that all inhabitants, both of present and future generations, without discrimination of any kind, can create cities and human settlements that are just, safe, healthy, accessible, affordable, resilient and sustainable, and inhabit them… ideal known as the right to the city”.

However, the Right to the City should not be considered an ideal but a real and necessary goal if the commitments made by the United Nations are to be achieved. Civil society, in partnership with many local governments around the world, has been working on this for decades. It is a bottom-up collective creation, from the grassroots, people from all over the world who fight, organize and defend the creation of spaces for everyone. It is the global alliances for exchange and support such as the Platform for the Right to the City that echo this work, as highlighted in ECOSOC’s latest report on the progress made in the implementation of the NAU, in paragraph 44. This same report also mentions the efforts to “enshrine the Right to the City” and establish coherence and integration between the world’s agendas (paragraph 10).

Why the implementation of Agenda 2030 and the New Urban Agenda should have a human rights perspective

The urban, housing and land crisis we are living in makes today’s world quite uninhabitable, a world in which profits and economic calculations are above the well-being, dignity, needs and rights of people and nature. This position has led us to the current scenario in which the housing crisis, the destruction of nature, the expulsion of people and communities from their homes, migration and the increase in the number of displaced persons and refugees, and so many other violations of rights make the list of challenges to achieving compliance with Agenda 2030 and the New Urban Agenda endless. If the current challenges are not reversed and the spaces where we live are not allowed to be places where the different needs are heard and specific responses are given, the commitments of Agenda 2030 and NAU will remain only in paper commitments.

The challenge is to “leave no one or no territory behind” and for this we must seriously incorporate the Right to the City approach, which connects human rights and allows for better implementation of Agenda 2030 and the New Urban Agenda. This will be the message that the Global Platform for the Right to the City will bring to the United Nations on the occasion of the High-Level Political Forum (HLPF), which aims to follow up on the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDOs), between 9 and 18 July this year.

At this annual meeting of states, the private sector, local authorities and civil society that monitors development activities in an integrated manner, the Right to the City will have its own programme within and outside the United Nations. As in so many other forums away from social movements and the problems of everyday life, we will focus our efforts on drawing attention to the local and global struggles of communities around the world that work every day to defend the right to the city, facilitating the participation of organizations and groups whose voices are often silenced or not heard. The Global Platform for the Right to the City will echo the denunciations, demands and proposals of the comrades of Abahlali Base Mjondolo, the largest post-apartheid urban movement in South Africa, who struggle for land and suffer persecution from the government; from the Maasai communities whom the Government of Tanzania has left homeless and face overwhelming levels of human rights abuses; to the families affected by the tragedy and fire in the building in Sao Paulo, to the communities evicted in El Espino, El Salvador, and to so many other struggles for the democratization of decision-making spaces, for the preservation and expansion of public spaces, and that no person or social group suffers discrimination.

There is a global demand from citizens for more participation in decision-making and greater access to the material, political and symbolic benefits that our cities and societies have to offer. The Right to the City poses: what city do we want? for whom is it made and by whom? We want to live in places that prioritise human rights.

The HLPF is an opportunity for civil society to participate in the process of monitoring and strengthening policies and partnerships for compliance with the ODS and NAU. It is a key moment to call for a political flag and a key tool such as the Right to the City, which responds to some of the most stifling challenges of our time by placing people, daily life, care, aspirations and human rights of each and every one, truly at the centre.

Article by Nelson Saule and Lorena Zárate, Global Plataform for the Right to the City