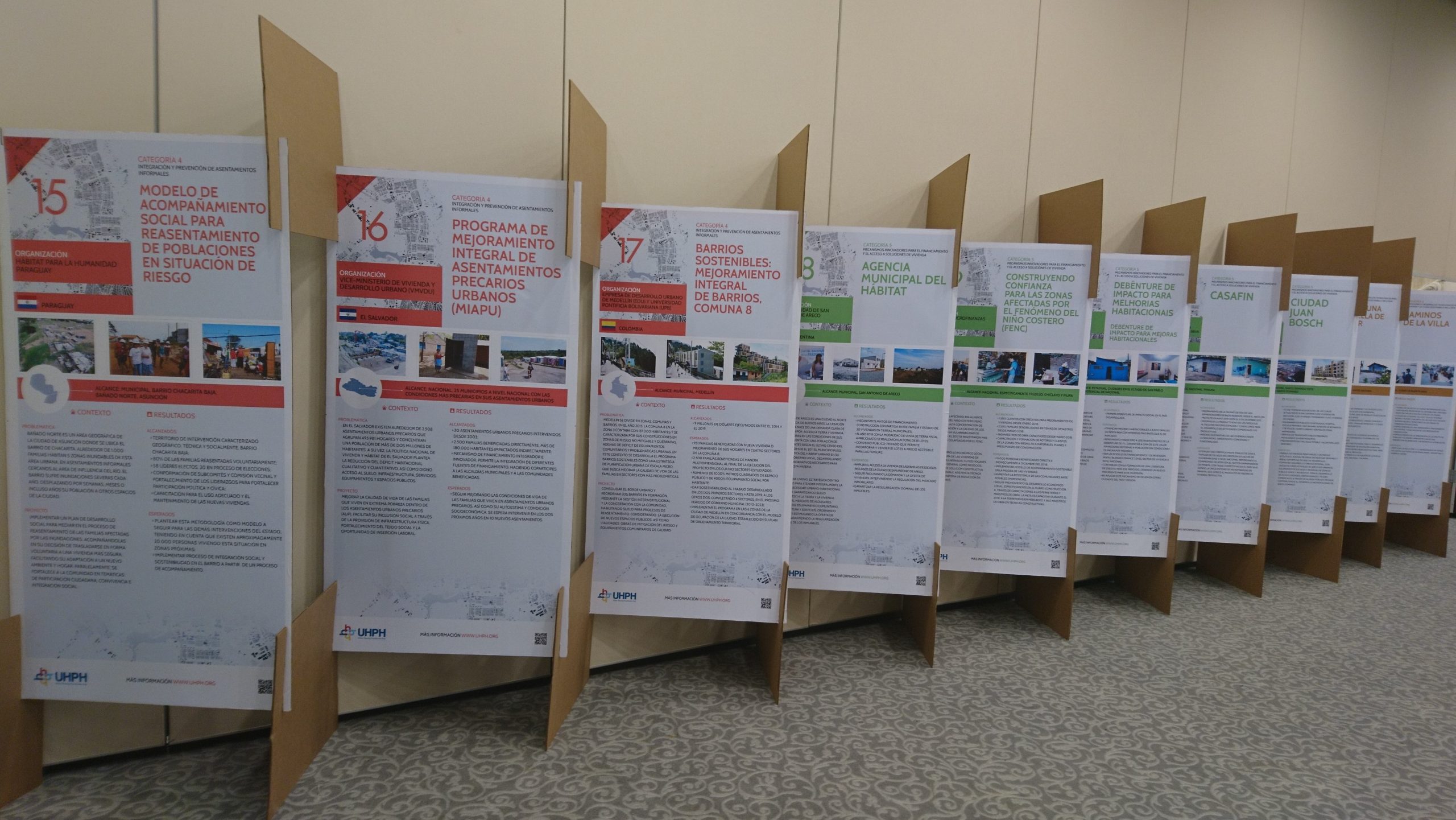

The Regional Housing and Habitat Forum that took place this past June in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic was an unusual gathering. It brought together strategic stakeholders related to the urban and housing agenda in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region and introduced them to29 inspiring practices that promote adequate housing and habitat as drivers for sustainable development in the region.

The 29 experiences were selected through a contest organized by Cities Alliance, Habitat for Humanity International, and UN-Habitat as part of the Urban Housing Practitioners Hub (UHPH).Some 300 applications were evaluated for their alignment with the principles of the New Urban Agenda – to which the Right to the City is central – and the top 29 selected.

I was fortunate to participate in the selection process for the contest and found the experience thought-provoking. I was impressed by how many high-quality practices there were in LAC that engaged multiple stakeholders, were multi-sector, placed people at the center, and pursued the fulfilment of the social function of the city. If the Inspiring Practices contest had been held 15 years ago, we wouldn’t have had such a wealth of integrated experiencesto choose from.

Why is this, and why in LAC? Perhaps it isthe result of a multi-year struggle in LAC for the recognition of the Right to the City in policies, legal frameworks, urban development plans, and programmes led by public and/or social sector. It is no coincidence that the LAC region led and pursued the inclusion of the Right to the City concept in the New Urban Agenda. Rather, it reflects a social and political engagement that has spawned a new generation of practices and stakeholders that share a different view of what and whom our cities are meant to serve.

Certainly, the inertia of old systems in place – such as laws, bureaucracy, and institutions – still represents a major frictional force when it comes to scaling up and replicating progressive endeavours. As renowned sociologist Saskia Sassen noted at the Santo Domingo Forum, unknown market forces are increasingly occupying cities around the world, leading to the question: Who owns the city?

The 29 selected and showcased Inspiring Practices were not the only elements of the Forum that highlighted the Right to the City. The concept was evident over and over throughout the debate in discussions on finance, or policy frameworks or climate change. By the end of the Forum, it was clear that we have compelling technical solutions at hand in LAC (although there is still a need to expand, build capacity, and add practitioners).

But the real shift towards a future where the New Urban Agenda is possible will only happen when we change the way we operate. We need more gender-balanced decision-making processes– centered on people with strong, genuine multi-stakeholder and multi-level democratic governance models –that enable the city to realize its social function at maximum andto significantly expand access to well-located land and public spaces to all citizens.

In a way, the debates in Santo Domingo will help regional (and maybe even global) practitioners and researchers to work and think about our cities in a different way, as it offered some tools and concrete examples of how to do so. Also, the Forum built wide-spread consensus around the main technical and political challenges to be tackled,with housing as a strategic – if not the most strategic – pillar to achieving the Right to the City as the global agendas are implemented.

Another important outcome of the Forum was the launch of the Urban Housing Practitioners Hub platform, which is supported by a multi-sector alliance of stakeholders that includesover 30 organizations representing national and local governments, NGOs, foundations, academia, the private sector, and international organizations.

The main objective of the UHPH is to function as a network of networks, a repository of practices and research on housing in LAC and a space to share, create consensus and generate a critical mass. Many UHPH supporters are also strong advocates for the Right to the City, creating robust links between the two platforms that we aim to strengthen along the road ahead.

In the near future, it will be critical for the Global Platform for the Right to the City to be able to “land” and translate its still-abstract concept into concrete experiences. This will help improve public understanding of how this collective and intangible right translates into practice.

Maybe this first tranche of selected practices can inspire case studies and/or further reflections that enhance and build on the Right to the City perspective.This is something that we can do jointly and, eventually, with help from research organizations and academia in the region. The UHPH is a regional public good and we should maximize its potential to solidify the Right to the City, especially now that all its elements are clearly expressed in the New Urban Agenda.

Article by Anaclaudia Rossbach, Cities Alliance