Article by HENRIQUE BOTELHO FROTA and LORENA ZÁRATE

Originally published in spanish in Crítica Urbana. Revista de Estudios Urbanos y Territoriales Vol.3 núm. 13

Derecho a la ciudad.. A Coruña: Crítica Urbana, July 2020.

“The right to the city has gained increasing attention in the public debate in recent years, being claimed by different groups and by civil society organizations. Even some governments (especially local ones) are beginning to adopt this right in their speeches and/or as a parameter of public policies”.

Weighing in on more than five decades of the famous book by Henri Lefebvre, who was the first to coin the expression “right to the city”, it seems that its strength as a collective claim has grown recently. The association between the right to the city and the insurgent movements mobilized in the streets is increasingly common. This indicates not only the actuality of the criticisms promoted by the right to the city in relation to the contemporary urban condition but especially the fact that this right carries with it a powerful mobilizing idea of transformation that continues to be important for feeding the utopia of a new society. Even more so in times of deep crisis of the models of occupation of territories like this one that we live in innumerable countries, aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The right to the city as a living utopia

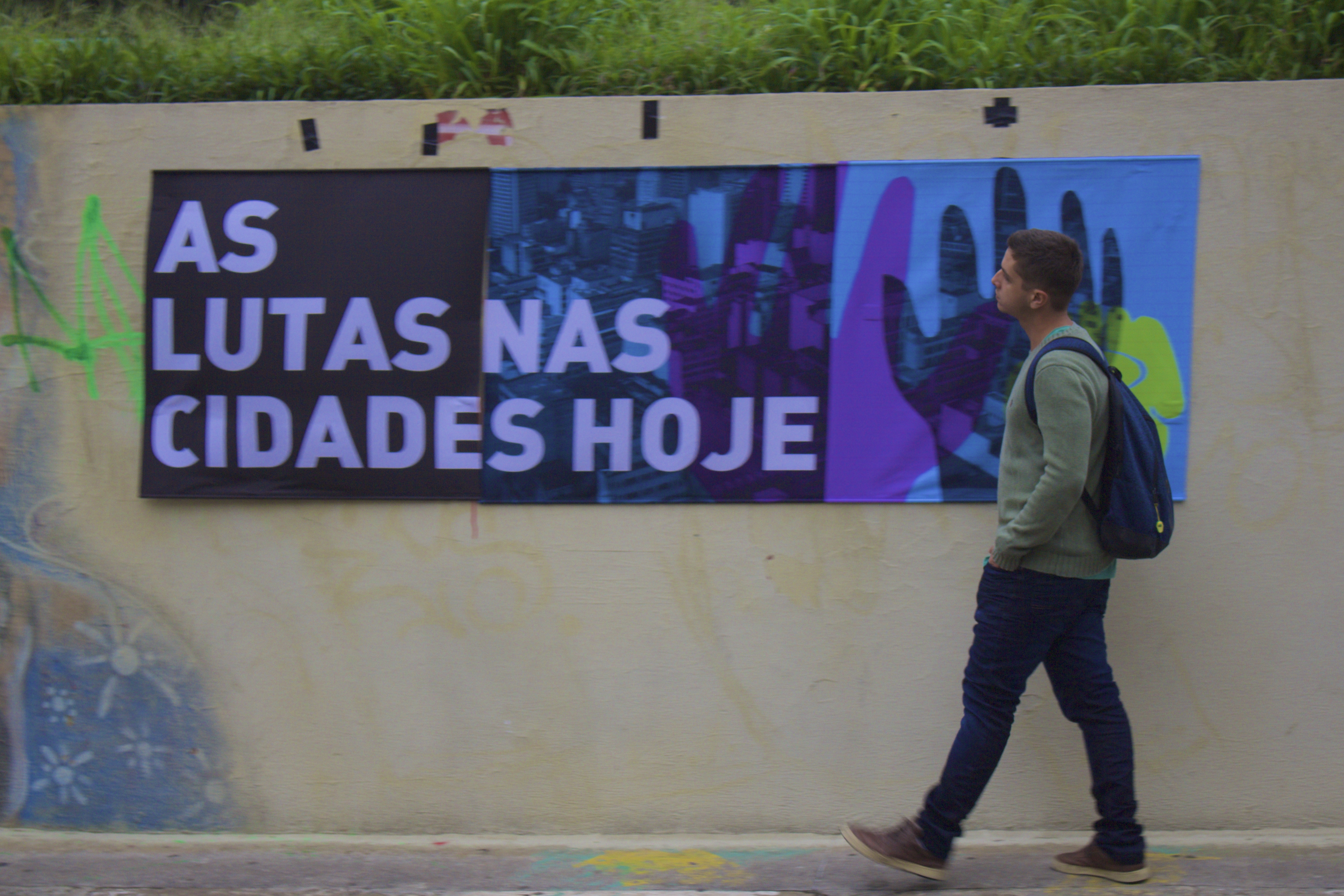

The relevance of the right to the city as a banner of current social struggles is explained by the fact that it was not frozen in the theoretical works of the 1960s and 1970s. It was taken by social movements in different parts of the world as a living utopia that is in constant development and construction.

Photo: Henrique B. FROTA

These social movements and their networks, allied with academic activists, have built a renewal of the right to the city agenda in the last three decades. They have added, over time, layers of criticism and struggle that were not present in the initial debates. And, with that, important references were produced that contribute to the advancement of the demands for a more just and sustainable life that values the common good.

Documents such as the Treaty for Cities, Villas and Democratic, Equitable and Sustainable Towns (1992); the Charter for the Right of Women to the City – Latin America (2004); the World Charter for the Right to the City (2005) and the Mexico City Charter for the Right to the City (2010); are examples of how these networks produce knowledge that serves the processes of social transformation and that is always renewed. This collective trajectory evidences some fundamental aspects for the understanding of the right to the city. The first is that the right to the city cannot be understood as a demand for infrastructure, urban services, or housing alone. These “benefits” can be provided very well without any breakdown to the segregated and space-exclusive mode of production.. Moreover, as much as collectives and social movements may have an origin linked to certain specific struggles (habitat, mobility, solidarity economy, gender equality, etc.), they understand that the struggle for the right to the city cannot be fragmented. This means that there is an aggregation force in the right to the city that is more than the simple sum of compartmentalized struggles. A second aspect is that the right to the city is, above all, a collective “political right” that is linked to the dimension of the struggle. It should not, therefore, be confused with a state urban policy, with an urban project, or with a specific legal framework. However, this does not mean that the recognition of the right to the city or some of its components in national legislation, in international treaties, or in official declarations is not part of the tactics of the struggles. These are important achievements and contribute to the enforceability of this right in legal and institutional forums. Its recognition as a “legal right” has been fundamental for the advancement of social conquests and for resistance processes in many contexts. Urban law, for example, has evolved greatly thanks to the work of jurists who have been defending the recognition of the right to the city in-laws and judicial decisions for years, which has allowed the development of progressive urban legislation in many countries and cities. Therefore, as Lefebvre himself pointed out, “while waiting for the best, it can be assumed that the social costs of denying the right to the city (and some others), assuming they can be counted, will be much higher than those of fulfilling them. Estimating the claim of the right to the city more ‘realistically’ than its abandonment is not a paradox. Therefore, the political and open dimension of the right to the city is not incompatible with its legal recognition.

Photo: Henrique B. FROTA

Segments that deny the enforceability of the right to the city, even within the framework of human rights, hinder the progress of social conquests. It is true that the right to the city does not adjust to the liberal vision of rights, being much more sophisticated and transgressive because it represents a collective proposal, but this does not eliminate its legal exigibility. The third aspect is that the right to the city always implies the spatial perception of inequalities. There is no racism, gender discrimination, LGBTQphobia, or exclusion of class outside of space. The imposition of patterns of segregation and violence against specific social segments is part of the social and political constitution of territories and the city, in accordance with the current urbanization model.

A Global Platform for collective struggles for the Right to the City

Following the historical trajectory, many networks and movements from different countries founded, in 2014, the Global Platform for the Right to the City. This network has presented itself as a promising possibility for dialogue and collective construction in favor of a less fragmented conception capable of strengthening struggles and nurturing a common utopia. After a process that involved numerous collectives from all over the world, the Platform assumed the following definition of the right to the city: The Right to the City is the right of all inhabitants, present and future, permanent and temporary, to inhabit, use, occupy, produce, govern and enjoy just, inclusive, safe and sustainable cities, villages and human settlements, defined as commons essential to a full and decent life. (GLOBAL PLATFORM FOR THE RIGHT TO THE CITY, 2018).

Although it deals with issues such as access to specific urban facilities, infrastructure, or housing, the main idea that drives the coalition is the possibility of building a city completely free of oppression. The components on which the concept of the right to the city is developed referring to the fight against all forms of discrimination, the construction of radically democratic political processes, and the break with the model of the commodification of space. It is based on a utopia of solidarity that recognizes and protects common goods. To give greater concreteness and show changes that build the idea of the right to the city, the Platform enunciates the following components, all of which are interrelated:

- A city free of discrimination with gender equality

- A city of inclusive citizenship in which all inhabitants, permanent or temporary, are considered as citizens and granted equal

- A city with enhanced political participation

- A city fulfilling its social functions

- A city with quality public spaces and services

- A city with cultural diversity

- A city with diverse and inclusive economies

- A sustainable city/human settlement with inclusive rural-urban linkages

And, as important as the content, a merit of the Global Platform that inherits from the popular processes, is the capacity to articulate different languages and tactics to expand the dialogue with as many actors as possible. Therefore, while focusing on technical forums on public policy or global multilateral institutions, it manages to articulate artistic languages, develop popular ways of strengthening capacities, and, above all, connect social demands with governmental bodies.

Walking forward

Despite the current growth of collectives that resignify the right to the city in their struggles and the important advances made by networks such as the Global Platform for the Right to the City, the road is still long. Our human settlements continue to be profoundly unjust, with millions of people around the world without even the slightest access to dignified living conditions. The exploitation of nature continues to lead our planet into an unprecedented crisis. Hegemonic systems continue to reproduce forms of social, economic, and political dispossession and discrimination. The crisis amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic shows how our cities are at the center of the problem. This reality indicates the size of the challenges we face in making cities part of the solution.

NOTE ON THE AUTHORS

Henrique Botelho Frota is a lawyer, human rights activist. Executive Coordinator of the Pólis Institute (Brazil) and member of the support team of the Global Platform for the Right to the City.

Lorena Zárate is a historian. Member of the support team of the Global Platform for the Right to the City.